Common COVID writing mistakes (and how to fix them)

Should COVID be in all caps? Is it quarantine or isolation? Learn how to write about coronavirus correctly

Welcome to year three of the COVID-19 pandemic. The fundamental changes that this disease has wrought upon our lives are truly mind-boggling—more than 5.6 million deaths, lockdowns and border closures, a huge mental health toll, disruption to supply chains and product shortages (not least toilet paper), and huge economic damage.

There’s another aspect of life that has been significantly affected by COVID-19: the English language. The pandemic has brought a plethora of words and phrases into common usage—some entirely new, some previously reserved for scientific and academic circles.

However, with this vocabulary explosion, there’s just as much confusion about the proper use of COVID-related terms. Luckily, the Outwrite blog is here to clear up some of the most common COVID writing mistakes.

Is it COVID-19, coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2?

First up is how you should talk about the virus itself – and you may be surprised to find out that most of us are getting it wrong. Technically, the following distinctions apply:

- Coronavirus can refer to any of the family of viruses that cause common colds, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) or MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome). They are named for the crown-like spikes on their surfaces. The virus that causes COVID-19 is just one type of coronavirus.

- SARS-CoV-2 is the actual virus that causes COVID-19. Technically, you don’t get a COVID test: you get a SARS-CoV-2 test.

- COVID-19 is the respiratory illness that’s caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (literally, COronaVIrus Disease 2019), not the underlying virus itself.

Is it OK to use these terms interchangeably?

The good news is that it’s become acceptable to use ‘the coronavirus’, ‘COVID-19’ or simply ‘COVID’ interchangeably, especially in informal writing. Most people will understand what you’re talking about if you use any of these words. However, if you’re drawing a distinction between the virus and the illness, it’s best to do so as follows.

- When talking about the virus: use ‘the coronavirus’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’ or ‘the virus that causes COVID-19’

- When talking about the disease, illness or symptoms: use COVID-19

You should definitely use the correct terminology if you’re writing in a formal register, or for academic or scientific audiences.

Should COVID be in all caps?

You may also see COVID-19 written as Covid-19. While the first version (capitalized) is preferred by the World Health Organization (WHO), both are acceptable and usually come down to the style preference of the publication or organization for whom you are writing. For example, the Guardian uses Covid-19, because its preference is to:

“use uppercase for abbreviations that are written and spoken as a collection of letters, such as BBC, IMF and NHS, whereas acronyms pronounced as words go upper and lower, eg Nasa, Unicef and, now, Covid-19.”

If there’s no style guide preference, it’s generally best to default to the WHO-preferred COVID-19.

Variants - aka ‘it’s all Greek to me’

The coronavirus has mutated into several new variants or versions over time. While initially they were referred to by variant numbers (like B.1.1.7) or by where the variant originated (‘the South Africa variant’), each specific variant of the coronavirus is now assigned a letter of the Greek alphabet by the WHO. The current major variants are Delta and Omicron.

You should use the Greek names (which may or may not be capitalized, depending on style guide preference) when referring to different variants. It’s best not to use the variant numbers unless writing for an academic audience, and the use of country labels is frowned upon.

Are you in quarantine or isolation?

The terms quarantine and isolation are often used interchangeably. They actually refer to two different reasons for being confined to your own home for days on end. The distinction is as follows:

- Quarantine refers to staying at home if you only think you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus—for example, if you are a close contact of a confirmed case. It’s a precaution in case an infection manifests.

- Isolation refers to being under house arrest because you know you’re infected, usually via a positive test result.

These terms shouldn’t be used interchangeably in anything but informal writing. You may even see the particularly Australian abbreviation ‘iso’ pop up in very casual writing.

Testing times

The ubiquitous ‘nose swab’ is something we’ve probably all become far too familiar with for the last couple of years. These can be called a coronavirus test or COVID-19 test in general writing. However, avoid using COVID-19 test when writing formally or for academic/scientific audiences (use coronavirus test or SARS-CoV-2 test instead).

There are three main types of coronavirus tests:

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test: The most sensitive test, this looks for the virus's genetic material and reproduces it in a lab until it's detectable by a computer. The test involves a nasal swab and/or sometimes saliva. Results can take a day or two, or longer. This should be referred to as a PCR test; it can also be called a lab test.

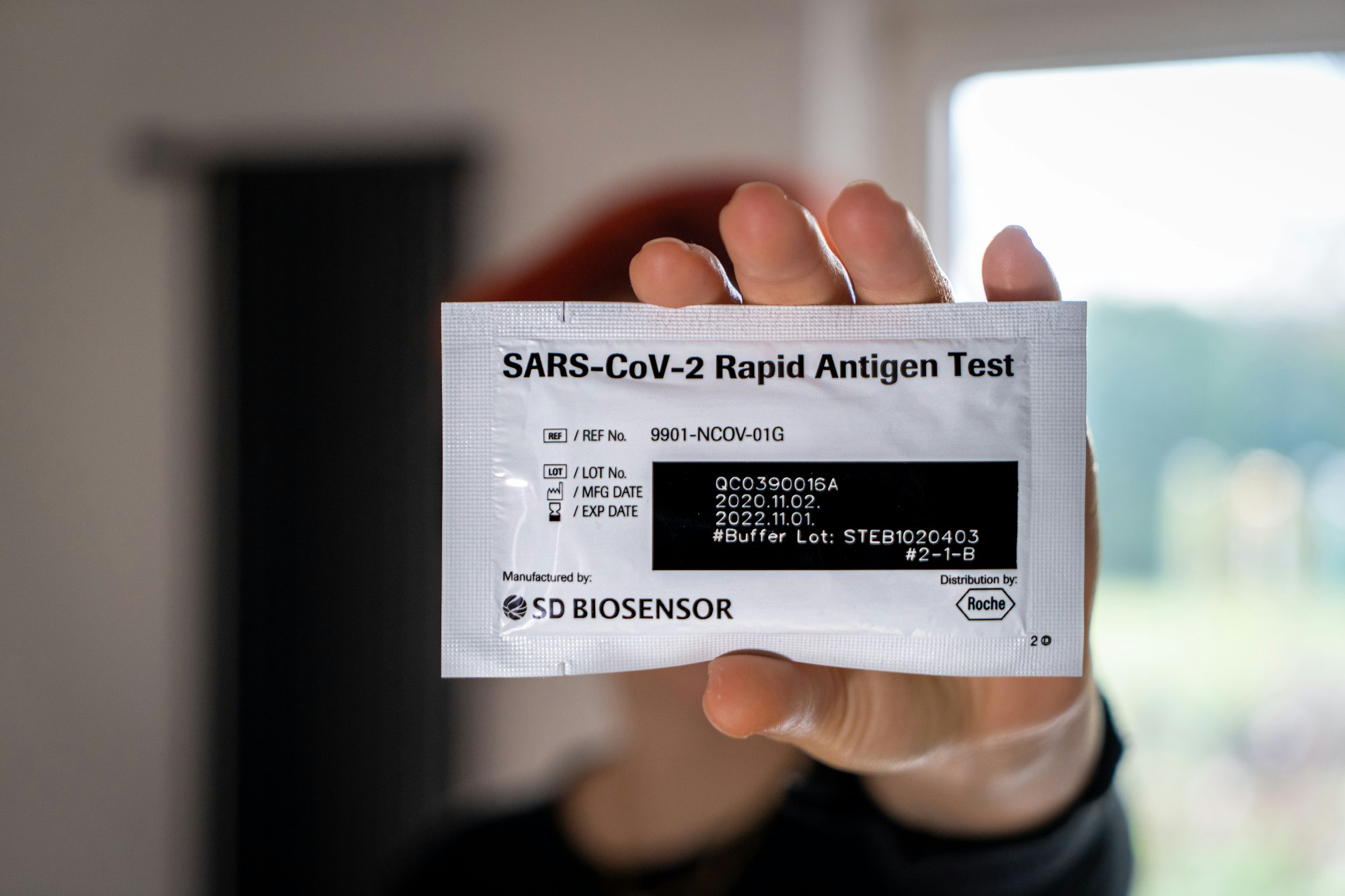

- rapid antigen test (RAT): This test looks for proteins found on the surface of the coronavirus, rather than the virus itself. It isn't as sensitive as a lab test, but can be done at home. Rapid tests are usually done with a nasal swab and take about 15 minutes to yield results. These should be referred to as a rapid test, home test or RAT. Do not use ‘RAT test’—this is a tautology.

- Antibody test: The third type of test checks for antibodies to the coronavirus, a sign that a person had an infection in the past or received a vaccine to spur immunity. These are usually just called ‘antibody tests’.

Vax facts

The language around vaccination may be second only to that around coronavirus: indeed, ‘vax’ was the Oxford Dictionary’s word for 2021!

You should use the terms coronavirus vaccine or COVID-19 vaccine when talking about vaccines, not anti-coronavirus vaccine or anti-COVID-19 vaccine. The terms immunization and vaccination can generally be used interchangeably. Note that immunization is spelled ‘immunisation’ in British and Australian English.

Vaccine manufacturer names should be spelled as follows:

- Pfizer

- AstraZeneca

- Moderna

- Novavax

- Sinopharm

- Sinovac

- CanSino

- Johnson & Johnson

Is it OK to use terms like ‘vax’, ‘fully vaxxed’ and ‘anti-vaxxer’?

The colloquialisms ‘vax’ and ‘vaxxed’ are okay to use in informal writing, but should be avoided in neutral and formal writing (unless part of a direct quote). The phrase ‘anti-vaxxer’ is quite inflammatory: it should be used with caution.

Further information

These are just a few of the words and phrases that the coronavirus has introduced into our vocabulary. Check out our A-Z of coronavirus reference guide for more common terms and how to spell them.

For more on the principles of writing for different audiences, check out our blog post on writing formality. Outwrite's paraphrasing tool can also help you rewrite sentences to make them more or less formal. Just highlight a sentence, choose a goal, and we'll suggest a list of alternatives. Head to our site to give it a go!